Even ideologies, which claim eternal principles of the right to life, liberty and property, are shaped to a significant extent by their time and its political conflicts. It becomes not least clear in a new history of ideas about libertarianism. Mattias Svensson has read.

SEPTEMBER 22, 2023

Tritnaha was the name of the black club that was run in the premises of the Freedom Front in the 1990s and which, when the politicians failed to close it down despite repeated raids, resulted in the 05 am open in the nightlife. The name was added when, in a debate a few years before, a populist twisted the word “libertarian” so badly that with a few more mispronouncements it became “tritnaha”. She literally had no concept of what a libertarian was – and was hardly alone in that.

A similar confusion is probably felt by those who read Matt Zwolinski and John Tomasi’s The Individualists: Radicals, reactionaries and the struggle for the soul of libertarianism (Princeton University Press, 2023), an ideological history of libertarianism. After reading, one knows that libertarianism can mean capitalism or anti-capitalism, left or right, anarchism or advocating a state, open borders or closed and isolated small communities, and being radical or reactionary. It certainly seems to be an intellectual trend in American universities at the moment to want to make every ideological label as diffuse and bland as possible, but Zwolinski and Tomasi at least make some good arguments along the way.

One of the more compelling is how much also ideologies with claims to eternal principles are in fact shaped by their times, and by what their advocates want to counter rather than what they are for.

This is clearest when Zwolinski and Tomasi go through the first phase of libertarianism, which they place in the second half of the 19th century. Here, there are big differences between European and American libertarianism, and the differences seem to depend to a large extent on what one is turning against.

For the European libertarians, socialism is the main antithesis. It is also, according to the authors, more about defending existing freedoms against new proposals for political intervention. The most brilliant thinker from this time was Frédéric Bastiat, whose economic reasoning was often a polemic against socialist proposals to use the state to intervene in the economy. Bastiat pedagogically shows why, for example, it is based on fallacies that the state creates employment and prosperity when it spends money – that is what you see, but what you don’t see is how people would have spent and invested the same money if they had been allowed to keep it. What we received from the state is not a service, but restrictions on what we could do.

In the United States, the leading libertarian thinkers were concerned about slavery.

In the United States, by contrast, the leading libertarian thinkers were primarily concerned with slavery. It led to a very different world of thought. The criticism of how people were enslaved in the American South made American libertarians more critical of the state, often anarchistic. They could also take the criticism of how people were exploited on plantations longer, and consider it wrong to make money by owning land and letting others do the work. It is an anti-capitalist line of thinking.

At the same time, it was clearly anti-authoritarian and libertarian ideas that also sprouted in the United States. Lysander Spooner demonstrated the inconsistency of the constitution by starting to compete with the government postal service. It was hindered by legal implications, but led to lower postage costs. A bit like when the pirate radio stations Radio Nord and Radio Syd in Sweden got the state monopoly to start P3 and start playing youth music. Others were committed to free love and criticized that the marriage forms of the time made the woman the property of the man. Such “free thinkers” were other examples of how the Americans differed from the European libertarians both in conclusions and in the choice of priority issues.

The point can undeniably be made that ideologies become different, also in parts of their foundations, based on which threats, problems and opposites they see.

***

However, Zwolinski and Tomasi find a number of points of departure that unite libertarians: private property, skepticism of authority, free markets, an understanding and appreciation of spontaneous orders such as language and markets that arise and function without being guided by any central intention or plan, individualism and negative freedom (ie a freedom from the intervention of others) and a social order built on voluntary social relations. They then describe libertarianism partly through positions on a number of factual issues and partly as consistently three phases: in addition to the initial one in the second half of the 19th century, it is about the Cold War phase with a gradual upswing in the post-war period, and the third phase which takes place after Fall of the Berlin Wall.

The book’s great merit is the ability to show how rich and sophisticated many of the arguments are nevertheless around the basic, common libertarian starting points. For example, when property rights are seen as a spontaneous order and woven into how it has worked to allow people to organize collaborations – a thought developed by FA Hayek and in the spirit of David Hume. The reasoning also takes nourishment from Thomas Paine’s and Henry George’s thoughts that private property can be legitimately established against a certain tax or charge to the public, which creates mutual benefits. What is important are predictable and stable rules for what people can do: Ownership of, for example, forests and factories requires decision horizons of many decades.

The authors also provide examples of how freedom, albeit indirectly, is the most important force in lifting societies out of poverty and discrimination. It’s about everything from Fredrick Douglas’s testimony about how, as an escaped slave, he saw work going on without either whips or swear words to motivate the workers (and description of how, when he loaded a ship in the harbor for wages and of his own choice, he felt the dignity of being one’s own master) to how countries became rich by abolishing guilds, opening up to free trade and discovering institutions such as the joint stock company.

The myth that libertarians do not see or care about discrimination and poverty is thoroughly debunked.

There is also a discussion about the role that state welfare commitments can have, as well as laws against discrimination on the basis of ethnicity or gender. But even in such discussions, the voluntary sickness and unemployment insurance policies that preceded state systems with rising prosperity are highlighted, and how civil society boycotts and protests overturned state discrimination laws and forced businesses to stop discriminating. Sheldon Richman also pointed out that this social involvement cooled when the state took over the issues of discrimination, and Walter Williams reminds that many blacks get stuck in welfare measures that mean continued poverty.

The myth that libertarians do not see or care about discrimination and poverty is thoroughly debunked, among other things, historian Richard Hofstadter’s widespread lies about the 19th century thinker Herbert Spencer are punctured . The difference is that libertarians do not see more government and new political measures as the obvious and only solution to social problems, not that they ignore the problems.

There are also some funny anecdotes. As in London in the winter of 1909, a variation on Dickens’s A Christmas Carol was made under the name A Message from the Forties . In this fairy tale, a merry Christmas is celebrated thanks to cheap imports from countries all over the world. Scrooge is the protectionist who made profits on his protected and more expensive products so that people could afford less. However, Scrooge is persuaded by the spirit of the free trader Richard Cobden to abandon protectionism, and so it can be a merry Christmas.

***

The book also has weaker sides. Especially when it comes to the description of third phase libertarianism. The authors here introduce three branches, where they themselves stand for one of them, the so-called bleeding heart libertarianism which has a greater tolerance for state welfare commitments. John Tomasi’s earlier book Free market fairness (2012) was an interesting synthesis of the thinking of John Rawls and Robert Nozick. The other branch is a kind of left-libertarianism with names like Roderick Long, who seem to argue, among other things, that companies like Walmart don’t deserve their profits because they’re earned on publicly funded road networks.

The third branch is the paleolibertarianism that has currently taken over, among others, the American Libertarian Party. This school of thought is portrayed critically but still fairly. During the 1980s and 1990s, the anarcho-capitalist Murray Rothbard wanted to mobilize rednecks for strategic reasons, “ordinary people” in the sense of not city dwellers. He came to turn against all kinds of personal freedoms, from free love to free drugs, because it was well-educated townspeople who espoused them and lived by such standards. Anarchism notwithstanding, he advocated more brutality from the police force and more obstacles to mobility than today. In contrast, paleolibertarians do not retain much of Rothbard’s earlier understanding of the plight of blacks, with everything from poor public schools to the fact that those who administered welfare systems and planned housing were often white, contributing to racial segregation.

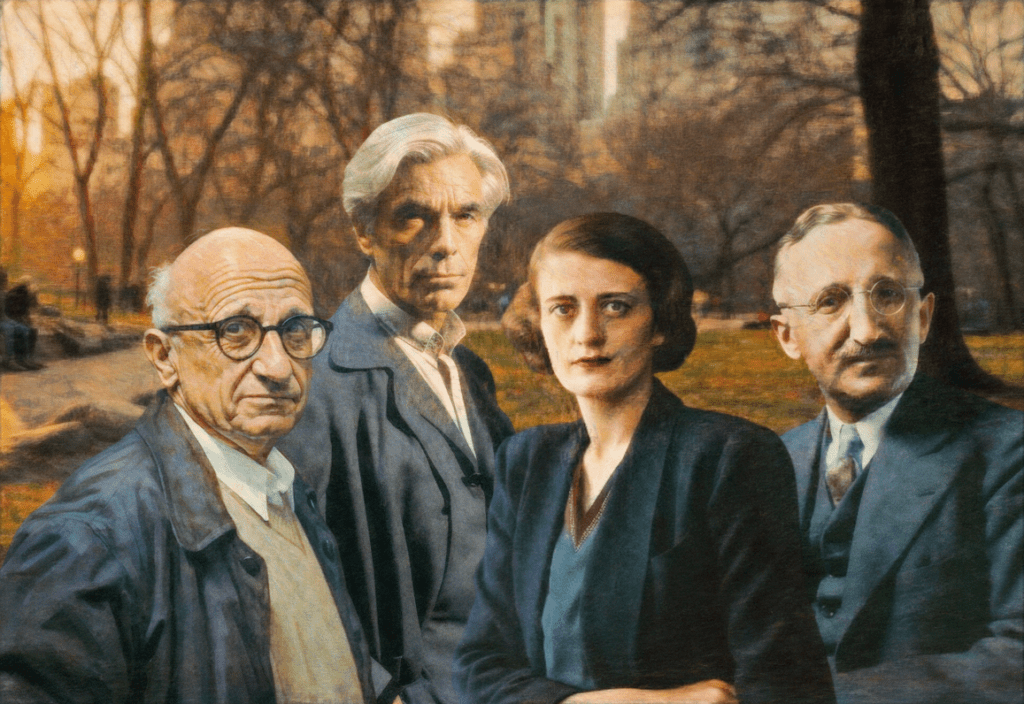

Third-phase libertarianism has a significant slant on post-war libertarianism and especially on the emphasis on economic freedom and the defense of Western capitalism. The criticism that these markets could and should have been freer, which would not have been as convenient for dominant corporations and their profits, is certainly correct. But the suggestion in the book that second generation libertarians like Ayn Rand or Milton Friedman would not have seen this is incorrect and untrue. In the background there seems to be an academic envy and pettiness towards intellectuals who have worked in the culture or at think tanks, even if it is dressed up as a criticism of such platforms having rich financiers.

Libertarianism has always sounded to me like an artificial term for what is essentially a fairly consistent liberalism over time.

In any case, history takes on strange proportions when two schools of thought that essentially revolved around the authors’ blog are given a lot of attention, while no one who managed what is called Cold War libertarianism, i.e. built on Hayek, Rand, Nozick, Friedman and others, is considered to have formulated, according to the authors a thought after the fall of the wall. To be able to reflect this, there is not, for example, a line about the war against terrorism, which can nevertheless be said to have characterized the 21st century, and which many leading libertarians around Reason, for example, devoted energy to criticizing. Contemporary history is certainly always difficult and the miss may be due to home blindness. But it also becomes a constructed definition of persuasion.

Libertarianism has always sounded to me like an artificial term for what is essentially a rather consistent liberalism over time, which certainly borrowed and was inspired by other thinkers in some parts and always had a tangible element of theorists who could end up a little all over the place in their conclusions. Personally, I have never been comfortable with the libertarian label’s carefree amalgamation of liberal ideas of limited state power and anarchist notions. Rather, I see liberalism’s limited monopoly on violence as opposed to free competition for the use of violence and patronage. This book certainly shows that anarchist libertarians had many good points in their social criticism, especially in their consistent opposition to slavery. But even Marxists can formulate good social criticism, and be right on individual issues.

At the same time, the book classifies Bastiat and his later followers – for example Herbert Spencer – as libertarians, in contrast to classically liberal intellectual predecessors such as John Locke, Adam Smith and David Hume. Zwolinski and Tomasi believe that libertarians have a strict application of roughly the same principles that for the classical liberal are more generally desirable, but with exceptions. At the same time, they adhere to two definitions of libertarianism where one is precisely the strict tenacity of principle (think Murray Rothbard, who deduced his entire anarcho-capitalism from the principle of self-ownership) while the other has one, at least compared to the rest of the political spectrum in the 20th century, far-reaching sympathy for free markets, property rights and freedom for the individual (think FA Hayek and Milton Friedman, both of which conceded a significantly greater role for the state than a minimal night watchman state with defence, police and judiciary). The latter definition, at least for me, is difficult to distinguish from classical liberalism. Or for that matter from what Zwolinski and Tomasi call Cold War libertarianism.

An alternative conclusion is therefore that classical liberalism was not just a phase, nor did it disappear after the fall of the wall – even if it was tragically weakened. That from an academic point of view, also apparently from libertarians with bleeding hearts, it constantly has to be declared dead or actively ignored, and at several points cannot even be reproduced correctly, speaks to the fact that the ideas are still alive. After reading The Individualists , I am more convinced that the term libertarian is a rather unfortunate construction, which has allowed incompatible parts to be given disproportionate space. But I am equally convinced that the core of ideas around which this book revolves is of vital importance to a civilized society.